[:it]

LA VIA PERFETTA

Il libro

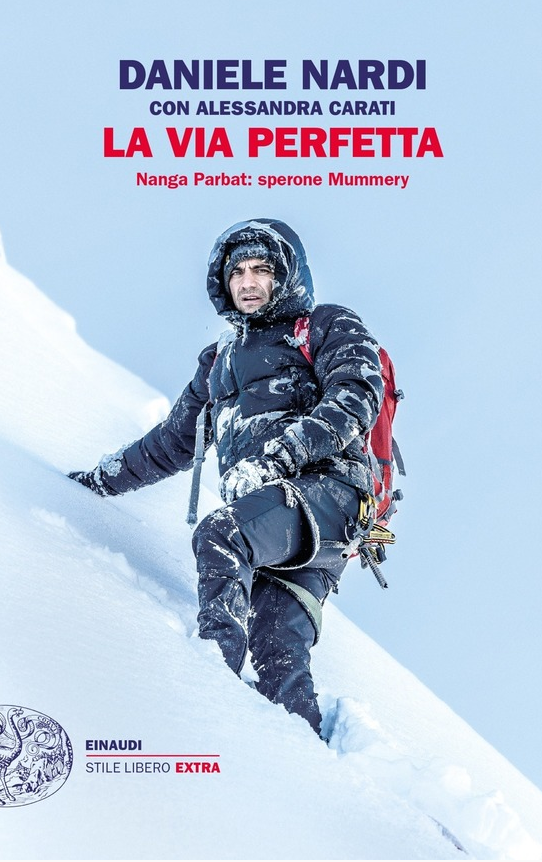

“La Via Perfetta / Nanga Parbat : sperone Mummery “ è il libro postumo di Daniele Nardi, scritto con Alessandra Carati ( scrittrice, editor e sceneggiatrice ) uscito a Novembre 2019 per Einaudi .

La tragica morte dell’alpinista laziale e del suo partner inglese Tom Ballard a fine Febbraio 2019 sullo Sperone Mummery del Nanga Parbat, ha trasformato quello che doveva essere il racconto di un lungo cammino verso un sogno, in un’autobiografia intima, piena di autocritica, sincera e consapevole, cruda nelle contraddizioni e amara nel racconto dei conflitti e nelle recriminazioni con gli altri ; nel contempo, piena di una passione inarrestabile, colma di amore per la propria moglie, di amicizia, stima e rispetto verso gli alpinisti con cui Daniele Nardi ha condiviso scalate impegnative, successi e fallimenti. Una storia piena di cadute e di successivi riscatti, contro avversità ben più temibili di qualche parete: malattie, fisiche e psichiche. Tutto questo, tra imprese alpinistiche di spessore crescente, certamente non da fuoriclasse e in ambienti non banali, di esplorazione vera, soprattutto su vette meno famose ma affascinanti e difficili tra 6000 o 7000 metri, di Karakorum e Himalaya.

Il gravoso carico emozionale e morale di completare e pubblicare il libro è stato preso sulle spalle da Alessandra Carati : senza precedente passione particolare per le Montagne, tantomeno verso l’alpinismo estremo, la sua conoscenza con Daniele Nardi – e con la sua famiglia, il suo ambiente nativo – si era trasformata in un’amicizia che l’ha portata a intraprendere il difficile trekking invernale verso il Campo Base del Nanga Parbat, per condividere alcune giornate con Daniele e Tom, nel Dicembre 2018 ; Alessandra ha voluto, non senza titubanze e problemi, provare veramente cosa significava l’alpinismo estremo invernale. La motivazione, lo spiega nell’intervista a seguire, era proprio capire cosa spinge un uomo a voler affrontare le brutali condizioni invernali su montagne colossali. Daniele, in quei giorni, le mostrò e poi le inviò un’email dove era scritto che se non fosse tornato dalla montagna voleva che lei finisse di scrivere il libro.

“Perché voglio che il mondo conosca la mia storia”

La prima, netta sensazione al termine della lettura, è che Nardi abbia scritto un racconto sincero , una vera “messa a nudo” – a differenza della gran parte dei libri scritti da alpinisti : pieni di retorica, autocelebrazione o noiosi trattati di motivazione , spesso mancanti di analisi di sé stessi ,delle proprie contraddizioni e miserie umane. Questo, assieme alla bella narrazione, è abbastanza inconsueto, visto che uno dei maggiori problemi di Daniele Nardi è sempre stato lo stile di comunicazione : spesso guascone e spaccone, carico di drammaticità, sopra le righe, amaro e a volte lamentoso , per la sindrome da isolamento sempre patita, lui alpinista “de Roma”, soprannominato “Romoletto” da Silvio Mondinelli, nei confronti dell’entourage alpinistico italiano, per la stragrande maggioranza “del Nord”. Con pochi sponsor e grandi difficoltà a finanziare le proprie imprese.

E’ sicuramente grazie al grande mestiere di Alessandra Carati che la lettura scorre piacevole, incalzante e appassionante ; l’impianto narrativo è ben strutturato sui cinque tentativi di scalata dello sperone Mummery del Nanga Parbat, il grande indice di roccia che punta dritto alla vetta dalla base del Diamir, circondato da canali di scarico, sovrastato da enormi seracchi glaciali, accessibile soltanto da un ghiacciaio pericoloso e crepacciato . L’incipit di questi tentativi è rappresentato da una mail, affettuosa e preoccupata, di un amico di Nardi, il grande alpinista canadese Louis Rousseau, che tenta di dissuadere il laziale dal progetto del Mummery, con parole e motivazioni toccanti e impressionanti.

Il Mummery : sogno e ossessione di Daniele Nardi , attorno al quale tutto il resto della vita scorre e avviene; per ognuna di queste prove, lo sguardo pensieroso dell’alpinista sulla parete Diamir si sposta e indugia sugli avvenimenti della sua vita, la sua formazione come alpinista, la prima solitaria sulle Grandes Jorasses a 19 anni, frutto di una incontenibile e precoce passione, sviluppata durante le vacanze estive della famiglia sulle Alpi, e maturata quasi da autodidatta, anche sulle friabili e non facili pareti nord dell’Appennino Centrale, sul Gran Sasso e sul Camicia.

Capace di raggiungere l’Everest nel 2004, seppur con l’ossigeno, poi la cima di mezzo dello Shisha Pangma senza ossigeno. Nel 2006 scala il Nanga Parbat per la via Kinshofer e il Broad Peak. Nel 2007 è capospedizione sul K2 e sale in vetta senza ossigeno – ma un compagno di spedizione, Stefano Zavka, non torna più dalla montagna , dopo aver raggiunto la vetta ben dopo il tramonto.

Nel libro traspare evidente l’autocritica di Nardi, inesperto nella gestione dell’emergenza e soprattutto del “dopo”, nel comunicare quanto è successo alla famiglia di Zavka. Un fantasma che lo accompagnerà a lungo. Il libro prosegue con i racconti asciutti sui passati successi , non indugia sulla descrizione alpinistica delle scalate – tranne per quella che Daniele Nardi ha più amato, la via nuova tracciata sul Baghirathi III con Roberto Dalle Monache, via non conclusa sulla vetta ma notevole nel suo sviluppo e nelle difficoltà su una delle più belle e ambite vette himalayane.

Paradossalmente, vincendo il prestigioso Premio Consiglio del Club Accademico Alpino Italiano per questa via, Nardi scrive nel libro che proprio qui cominciano “le interferenze” al puro amore per l’esplorazione dell’alta montagna : il suo desiderio di sentirsi accettato e riconosciuto da un ambiente che non lo considera quanto vorrebbe, la sua voglia di rivalsa, la necessità di visibilità cominciano a intaccarne la mente.

La storia dei tentativi di realizzazione del suo sogno, la via dello Sperone Mummery – obiettivo per cui è stato deriso, additato come suicida, esaltato, illuso anche dopo la morte – prosegue tra belle pagine di montagna : specialmente nel racconto del primo tentativo, esaltante del 2013, effettuato in coppia con la grande alpinista francese Elizabeth Revol ; il duo toccò il punto più alto mai raggiunto sul Mummery, 6450 metri, a circa 250 metri dalla fine delle difficoltà tecniche e dall’uscita dello Sperone sul “grande bacino”, il plateau a 7000 metri, tra le impressionanti colonne, severe e pericolose, dei seracchi glaciali incombenti . Sono poi narrate le vicende della mancata spedizione assieme a Tomek Mackiewicz ed Elizabeth Revol, il conflitto di visioni e obiettivi che li separa al Campo Base del Diamir ; conflitto che viene mitigato, dalle belle parole che Nardi riserva ad entrambi, piene di grande affetto e stima.

Il capitolo dedicato alla clamorosa rottura con Alex Txikon e Ali Sadpara a inizio 2016 , suoi compagni l’anno precedente nel tentativo di Prima Invernale fallito a duecento metri dalla vetta, è un racconto assai dettagliato di un “conflitto annunciato” a livello umano : i tentativi di Nardi di mediazione tra Bielecki e Txikon, con quest’ultimo assillato da problemi economici, l’incidente in parete dove salva la vita allo stesso Bielecki ; la evidente scarsa motivazione di Nardi per la Kinshofer, i primi conflitti con Txikon e Sadpara e la reciproca diffidenza, da subito, con Simone Moro , il fallimento di Elizabeth Revol e Tomek Mackiewicz quando a circa 7300 metri, con la concreta prospettiva di arrivare in vetta per la Messner-Eisendle, si ritirano ricevendo da Moro previsioni del tempo rivelatesi errate, forse la più strana vicenda avvenuta quell’anno . Confermata da Filippo Thiery, meteorologo di Nardi, che gli comunicò che era previsto bel tempo per 3 giorni ; si domandava come Karl Gabl – meteorologo di fama, da sempre di fiducia per Moro – avesse potuto sbagliare la previsione [ vedi le previsioni di quei giorni]. Mentre la francese e il polacco scesero velocemente i il 22 Gennaio , il 25 Gennaio Nardi, Txikon e Sadpara erano a C3, a 6700metri, con bel tempo . E la Revol abbandonò il Nanga : non aveva più tempo per riprovare la vetta. La coda polemica e di rottura tra Mackiewicz e Moro fu ancora più amara[ vedi Fonti (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)]

Poi la decisione di Moro e Lunger di aggregarsi alla via Kinshofer. Daniele Nardi ha aspettato tre anni prima di spiegare come secondo lui si arrivò prima alla decisione, poi alla rottura col resto del team, i conflitti con Txikon, la sfiducia totale di Moro vedendo Nardi che registrava i dialoghi , consegnando alla Carati le registrazioni audio al Campo Base e la sua versione. Versione assolutamente discutibile, ovviamente, e di parte : ma nel libro c’è anche questa. E c’è una ulteriore critica a Moro per aver lasciato la Lunger ritirarsi da sola, in difficoltà, il giorno fatidico della Prima Invernale sul Nanga Parbat.

Al tempo, seguendo quella spedizione giornalmente, non mi sorprese la sfiducia nei confronti di Nardi da parte di Txikon, di Sadpara e infine di Simone Moro, fino alla sua estromissione dal team . Ma nessuno esce indenne da errori e comportamenti ambigui, in questo capitolo , pur con diverse sfumature. E’, ovviamente, la sua versione : c’è tuttavia il particolare, non trascurabile, che i dialoghi sono fedeli trascrizioni di registrazioni audio, moralmente discutibili come ammette lo stesso Nardi, ma la co-autrice e l’editore Einaudi hanno ritenuto lecita e trasparente la loro pubblicazione [ podcast dal minuto 44:00 , intervista ad Alessandra su Radio24 ]

A tutt’oggi sono usciti diversi articoli della stampa specializzata sul libro ; è curioso, eufemisticamente parlando, notare che nessuno abbia avuto la curiosità di fare o farsi domande su questo capitolo scomodo, amaro, discutibile ma che è parte integrante, e ampia, del libro che Nardi ha scritto.

Al lettore ogni riflessione o giudizio proprio, su una questione che non cambierà più nulla : la Storia è scritta e ha cancellato vecchie polemiche. Questo capitolo della vita di Nardi svela un lato spiacevole che si preferisce generalmente occultare ; spoglia l’alpinismo dalla sua supposta idealizzazione , il suo essere non esente, come nessuna attività sociale umana lo è , da grandi rivalità, scorrettezze, miserie e opportunismo. Anzi : amplifica a dismisura pregi, qualità e paure, difetti. Di tutti, nessuno escluso.

Certamente, Nardi non è stato capace di diplomazia e autocontrollo nei rapporti di “peso”, in spedizione. Ha pagato caro, questa sua spigolosità, anche in termini di credibilità. Va detto.

Il capitolo del “Quarto Tentativo” prosegue col racconto della conoscenza con Tom Ballard, che cercò Daniele Nardi, interessato al suo tipo di alpinismo : un’amicizia che si saldò nel 2017, in una bella spedizione nel Ghiacciaio remoto del Kondus, in Karakorum, una via di roccia su un 6000 sconosciuto e un tentativo su una montagna di 7000metri iconica, il Link Sar. I due, dopo aver aperto oltre 1500 metri di via sino alle prime difficoltà della parete Nord Est, si dovranno ritirare tra valanghe e maltempo continuo. Poi c’è il capitolo, doloroso, della tragedia di Tomek e il salvataggio di Elizabeth, dove Daniele contribuì in modo concreto, coordinando e coinvolgendo tutti i suoi contatti pakistani e fornendo indicazioni utili . I pensieri su Tomek, sulla sua personalità e la sua intima anima di sognatore, sono molto toccanti.

Nel capitolo finale cambia il registro narrativo del libro: a raccontare, in prima persona, è Alessandra Carati.

Ripercorre il trekking al Campo Base, le difficoltà e il gelo, la sua intima esperienza come donna nel rapporto con i locali, l’enorme stima e rispetto che tutti i pakistani tributano a Daniele, la consegna di materiali e beni umanitari nei poverissimi villaggi tra Skardu e la Valle del Diamir ; l’amicizia e il buon umore tra Tom e Daniele, i paurosi rombi delle valanghe che scaricava la montagna “la cui mole copre il cielo e ti sovrasta immensa”. Poi il ritorno in Italia, i messaggi fiduciosi di Daniele e quelli preoccupati per il materiale sepolto dalle valanghe.

Fino al momento decisivo : c’è una finestra di tempo discreto, è il 22 Febbraio, ormai da un mese i due sono fermi al Campo Base, allenandosi sui sassi facendo drytooling, camminando fino solo al Campo 1. Partono di gran lena e determinazione, fino al fatidico 24 Febbraio, dove salgono 300 metri di sperone dai 6000mt del C4, una tendina in parete. Sono ottimisti, pieni di gioia che comunicano ad Alessandra per satellitare, hanno trovato il sacco appeso in parete, in alto. Ma si sono sforzati forse troppo nei due giorni precedenti, con una tirata e tanto carico di materiali per l’attacco decisivo. E le ore finali , il silenzio.

Tom Ballard e Daniele Nardi , Nanga Parbat

Tom Ballard e Daniele Nardi , Nanga Parbat

L’epilogo lo conosciamo , Alex Txikon generosamente parte dal K2 con una squadra per soccorrere e cercare Daniele e Tom. Dopo giorni tremendi, tra ricognizioni a piedi e coi droni, mentre infuria un brutto dibattito mediatico, dove Messner, poi Moro e altri affermano la sicurezza che i due siano stati sepolti da una valanga, che la via era quasi suicida [vedi sezione Fonti sotto],che Tom era stato coinvolto in una impresa non sua e non era da farsi come prima esperienza su ottomila, le tifoserie sui Social eccetera – i due sfortunati alpinisti vengono avvistati, morti, non travolti da una valanga ma appesi alle corde, probabilmente vittime di un incidente in discesa e ipotermia. La loro ultima telefonata pare fosse stata alle 20 di sera del 24 Febbraio , al Campo base: Daniele diceva che scendavano, le condizioni terribili. Qualunque fosse il motivo di abbandonare la tenda e sapere di andare incontro a ipotermia scendendo al buio, era evidentemente una tragica ed estrema necessità.

Il breve epilogo è una testimonianza di vita, di sensazioni pure e sublimi sul Nanga e si conclude così :

“almeno una volta nella vita, a tutti dovrebbe capitare di incontrare un Daniele Nardi che con un sorriso ti spinge ad andare a vedere cosa c’è oltre la linea dell’orizzonte, e a camminare insieme a lui sul ghiacciaio”

Daniele Nardi è uscito di scena con i suoi tanti difetti, la sua umanità brusca, diffidente, difficile e ambigua ; allo stesso tempo espansiva, positiva, piena di amore e di una incontenibile passione verso l’alpinismo e di sfida costante nell’affrontare i propri demoni. Una passione bruciante che gli è costata una breve vita – ma non vissuta da incosciente.

Una vita che merita rispetto, che suscita e susciterà discussioni ma una vita degna: un uomo, alpinista che ha avuto coraggio sia in montagna che nel lasciare testimonianza, soprattutto, delle sue più intime debolezze senza smettere di pensare positivo, di cercare di rialzarsi a ogni caduta per ricominciare e migliorare ; che nella Storia dell’Alpinismo rimarrà come colui che ha tentato “una incredibile via invernale, direttissima, una via fottutamente visionaria su una delle montagne più temute del mondo” – come ci ha scritto l’alpinista Louis Rousseau : la Via dello Sperone Mummery.

Intervista alla co-autrice : Alessandra Carati

Alessandra, il tuo è un curriculum solido di esperienze nella scrittura per il cinema e il teatro e poi come editor e ghost writer su progetti editoriali molto vari ; nel 2016 sei stata coautrice, con il ciclista Danilo Di Luca, del suo libro autobiografico “Bestie da vittoria”, un duro atto di accusa (e autoaccusa) , di chi non ha più nulla da perdere e può finalmente parlare in vera libertà del “sistema” nei confronti del gigantesco problema del doping, un disvelarsi intimo di un’atleta che si confronta con l’ipocrisia di chi lo ha espulso dall’ambiente (squalificato a vita ) come capro espiatorio unico di quello che sembra un’intollerabile groviglio omertoso di interessi collettivi nello sport. Cito questo tuo impegno letterario perché ho l’idea che in parte l’incontro con Daniele Nardi ti abbia coinvolto e convinto a lavorare con lui, per la sua esperienza – altrettanto problematica, anche per diverse ragioni – nell’ambiente a cui ha dedicato la sua vita : l’Alpinismo . E’ così ? Quale è stata, comunque, la spinta decisiva – per una autrice assolutamente distante e non coinvolta da una passione personale per la montagna – a intraprendere la scrittura di un libro con un’alpinista ?

Quando mi sono accostata alla storia di Daniele, non conoscevo l’alpinismo e non sapevo nulla sulla qualità dell’ambiente. Ho scelto di abbracciare il progetto perché Daniele mi incuriosiva. Come ho scritto nel libro e come molte altre persone, mi chiedevo perché qualcuno scegliesse di mettersi così duramente alla prova, su una montagna di 8000 metri, in inverno, per cinque volte consecutivamente. Volevo capire che cosa lo muoveva, intimamente e come essere umano.

Leggendo il libro, ho trovato straordinario il coraggio di Daniele per la cruda e sincera auto analisi, che non risparmia dettagli inediti su un suo periodo di depressione e burnout , non si fa sconti sugli errori nella vita privata così come quelli in alcune spedizioni, a causa del suo carattere molto difficile. Eppure, il lato positivo, di pura passione sincera, guascone ed empatico emerge e si fa apprezzare. Come hai vissuto questo aspetto contradditorio di Daniele ?

Daniele era tante cose insieme. La scrittura, per fortuna, resiste alla tentazione di ridurre in modo semplicistico le persone e mette al riparo dal giudizio. Così facendo ci permette di comprendere di più, accettare di più, amare di più.

Mentre lavoravate al libro, hai dovuto litigare con lui su come voleva esporre le sue emozioni, le sue idee e i fatti accaduti nelle grandi montagne di Karakorum ed Himalaya ?

Non c’è stato il tempo di confrontarsi sulla forma con cui costruire il racconto. Abbiamo lavorato insieme nella raccolta e nella scelta dei materiali, poi ho proceduto alla scrittura da sola, con tutte le decisioni che ne discendono.

Non posso non affrontare un tema molto delicato e scottante. Da quando è uscito il libro, ho letto articoli e recensioni ma per chiunque lo abbia letto, c’è stato un silenzio quasi totale e assordante su una parte precisa: il Tentativo Quattro, ovvero la spedizione 2015-2016 con Txikon e Sadpara, vissuta tra polemiche amare ; quello che stupì, all’epoca, è che Daniele si difese molto tenacemente soltanto dalle accuse di Txikon (poi rivelatesi piuttosto labili e infondate) di mancata contribuzione economica o addirittura di essersi “inventato” la caduta sul muro Kinshofer . Daniele non replicò, puntualmente, alle forti accuse di Moro.Questo pesò molto nel giudizio collettivo verso di lui. Così come Daniele stesso scrive.

Nel libro hanno colpito i dialoghi brutali e polemici di quanto accadde . E divergono rispetto alle versioni di Simone Moro. Ho ascoltato la tua intervista alla trasmissione di Alessandro Milan su Radio24, dove affermi che i dialoghi sono riportati “alla virgola” perché provengono dalle registrazioni che Nardi ha fatto nella tenda comune, mentre era in corso la riunione definitiva con tutti gli altri. Che la cosa non è affatto illegale, tant’è che Einaudi l’ha valutata pubblicabile senza censure. Lo confermi ? Qualcuno ti ha contattato per precisare o smentire quanto è scritto ? Cosa pensi della reazione della stampa, a proposito?

Le scene del quarto tentativo, che si svolgono nella tenda e in cui sono presenti Simone Moro, Alex Txikon, Tamara Lunger, Alì Sadpara e ovviamente Daniele, sono state ricostruite interamente a partire dalle registrazioni che Daniele aveva fatto. Non ho tratto le battute e il loro contenuto da un racconto mediato da Daniele, ma direttamente e fedelmente dagli audio. Sono le voci dei protagonisti.

Per esempio c’è un particolare del racconto su cui sono state date versioni discordanti, ed è il modo in cui si uniscono le due spedizioni. Moro ha dichiarato pubblicamente, nel suo libro ‘Nanga’ e in alcune interviste, di essere stato invitato da Alex Txikon, mentre negli audio ripete più volte che è lui a chiedere di potersi unire, tanto che insiste su quanti soldi deve pagare per il materiale e il lavoro fatto nell’attrezzare la montagna. È una differenza sottile, eppure sostanziale, perché definisce i rapporti di forza, i pesi e gli equilibri all’interno della squadra che tenterà la prima invernale del Nanga Parbat. Nessuno finora ha chiesto conto in alcun modo di quella parte del libro, tantomeno ne ha parlato la stampa. In onestà, se fossi un giornalista, sarei incuriosito, farei delle domande.

Veniamo alla parte più emozionante e dolorosa, quella che hai praticamente scritto da sola. Il tentativo finale: la tua decisione di fare il trekking e passare giornate al Campo Base per vivere veramente l’esperienza di una spedizione invernale ; l’atmosfera tra Daniele e Tom, le lunghe attese e il finale tragico.

Come hai vissuto quei terribili giorni? Hai pensato di mollare tutto, nonostante la richiesta di Daniele nella sua famosa email?

Durante le settimane dei soccorsi il progetto del libro non mi sfiorava nemmeno, ogni energia, ogni pensiero erano per Daniele e Tom. Mi angosciava saperli persi dentro il gigantesco massiccio del Nanga. E poi c’erano Daniela e Mattia, non riuscivo nemmeno a immaginare cosa potessero sentire in quel momento.

Più avanti sono stata tentata di lasciar perdere, ma la volontà espressa da Daniele era chiarissima e il suo mandato mi inchiodava. Avevo dato la mia parola.

Quale conclusione, se mai ci sia, hai elaborato nella tua anima, riguardo alla vita e alla morte di Daniele?

Non ho conclusioni, idee, tantomeno opinioni, sulla morte di Daniele. Tutto quello che ho sfiorato, intuito e a cui ho tentato di dare forma è dentro il libro. Ogni lettore può muovere da lì per lasciare emergere il sentimento con cui guardare alla sua figura, alla sua vita.

Intervista a Louis Rousseau

Louis Rousseau è uno dei più forti alpinisti canadesi . E’ nato nel 1977 nel Quebec e ha cominciato a scalare a 15 anni. Tra il 1999 e il 2010 ha arrampicato moltissime cime sulle Ande, accumulando esperienza sui 6000. Dal 2007 ha cominciato a scalare le grandi montagne del Karakorum e dell’Himalaya, aprendo una parziale via nuova sul Nanga Parbat nel 2009, ha tentato una via nuova invernale sulla parete Sud del Gasherbrum I. Ha scalato Gasherbrum II , Broad Peak e tentato varie volte il K2. Ha scalato 7000 come il Khan Tengri e il Tilicho Peak . Sempre senza ossigeno, perseguendo lo stile alpino e un’etica molto ferrea. Ha scalato assieme ad Adam Bielecki, Gerfried Goschl,Alex Txikon, Rick Allen e tanti altri.

Che rapporto hai avuto con Daniele Nardi ?

Non ho mai conosciuto Daniele di persona. Dal 2015 abbiamo avuto contatti sporadici via internet. Ho sentito parlare di Daniele dopo la via al Bhagirathi III del 2011 e del tentativo invernale del 2013 con Elizabeth Revol. Dopo di che, Alex Txikon mi ha contattato per unirsi a lui, Daniele e Ali Sadpara per il tentativo invernale di Nanga Parbat nel 2016. Ho detto di no. Daniele mi ha invitato per il tentativo di Nanga 2019 ma ancora una volta ho declinato l’invito e ho cercato di convincerlo a non ripartire. Durante la spedizione abbiamo avuto contatti regolari via WhatsApp, soprattutto quando hanno perso un sacco di attrezzature [seppellite dalle valanghe,ndR]. Gli ho proposto di spedirgli alcune attrezzature dal mio deposito in Pakistan. Dopo tutto ciò, erano ok, avevano l’essenziale per continuare la loro ascesa.

Cosa ne pensi di Daniele, quali impressioni e sentimenti lo hanno dato a te – come scalatore prima, poi come uomo?

Era un alpinista davvero motivato e orientato all’obiettivo. Sapeva arrampicare sia su percorsi tecnici e difficili tanto quanto aveva ottime prestazioni in alta quota. Durante i nostri dialoghi, ho realizzato che era un uomo molto gentile. Molto idealista, un sognatore che voleva sempre migliorare e tendere ad essere una versione sempre migliore di sé stesso. Durante la nostra ultima conversazione mi ha detto una cosa importante, che voleva “cercare di aiutare le persone a cambiare la loro vita ispirandole”. Quindi di sicuro Daniele era un uomo che voleva cambiare il mondo che lo circondava : non si trattava di alpinismo, di raccogliere cime o cercare le prime salite, era molto più una ricerca intima e personale.

So che ti ha chiesto di unirti al suo sogno sul Nanga, il Mummery ; poi, dopo uno scambio di mail gli hai detto che non volevi partecipare e gli hai chiesto di ripensarci. Puoi spiegarmi meglio, dopo la tua via nuova aperta sul Nanga nel 2009, cosa ti ha spinto alla decisione che avevi chiuso con quella montagna?

Inizierò la mia risposta con qualcosa che ho scritto a Daniele : “Lo troverete un po ‘esoterico, ma credo nella maledizione della montagna killer. C’è qualcosa sul Nanga Parbat che ci acceca come alpinisti e ci attira ancora di più verso il pericolo rispetto agli altri 8000m. Penso che sia a causa di tutto il folklore intorno a questa montagna. Si inizia a leggere molto su questa montagna che si trasforma in fascino e passione. E ‘davvero attraente e nasce il desiderio di andarci. Quando però fui lì nel 2009, due alpinisti hanno perso la vita e dopo ci fu molta discordia, a riguardo. La storia recente dei tentativi invernali è piena di discordia, incidenti, giochi dietro le quinte e ora morti. È una vera tragedia. Non ci sono altre parole per descrivere gli ultimi anni. Basti pensare all’attacco terroristico del 2013. Ho visto Daniele “entrare” in questo spirito e volevo fare qualcosa per scoraggiarlo. Gli ho chiesto se avesse voglia di trovare, con me, un progetto completamente diverso e positivo, ma lui mi rispose : “se cambi idea e vuoi unirti a me e Tom, fammelo sapere.”

Pensi che per un’ alpinista, il pericolo inizia nel momento in cui è troppo coinvolto per una montagna, un obiettivo particolare?

Per un’alpinista, il pericolo inizia non appena entra nella jeep che lo porterà all’inizio del trekking verso il Campo Base ; il che significa che sin dall’inizio della spedizione ci sono pericoli. L’alpinismo è uno sport estremamente pericoloso. Non ci sono molti altri sport in cui si va in vacanza e si torna senza un tuo amico. Però, anche se ci si sente “troppo coinvolti emozionalmente” per un progetto o una montagna, questo non significa che ci si trovi in un pericolo maggiore. Questo può influenzare il nostro processo decisionale? Certamente sì, quando ci sono altri obiettivi oltre all’arrampicata e al sentirsi liberi, anche obiettivi che non ammetti a te stesso. Porterai sempre in una spedizione le cose che non hai risolto a casa. Nulla di ciò che farai in montagna può risolverli, al contrario.

So che Daniele e Tom erano professionisti e hanno voluto scalare il Nanga Parbat, in inverno, per una nuova via, purtroppo hanno avuto un terribile incidente. Non sapremo mai esattamente cosa è successo ed è terribile per le famiglie. Più di ogni altra cosa, non sapremo mai il loro stato d’animo prima dell’incidente. Fu una distrazione, è stato il risultato di decisioni errate, un incidente in montagna? Non lo sappiamo. Quello che sappiamo è che i due alpinisti erano veramente esperti e si completavano a vicenda molto bene . Daniele aveva una solida esperienza di alta quota in ambiente invernale e Tom era uno dei migliori alpinisti su ghiaccio del mondo. Non credo che il loro stato emotivo abbia avuto nulla a che fare con la loro morte. È stato un tragico incidente.

Fonti e bibliografia varia

Daniele Nardi

Nanga Parbat ed Elizabeth Revol, primo tentativo al Mummery : http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201212505/Nanga-Parbat-Diamir-Face-Mummery-Rib-winter-attempt

Translimes Expedition con Tom Ballard, Kondus Glacier, Link Sar :

Farol West,unclimbed peaks in Karakorum :

Baghirathi III :

Thalay Sagar, con Alex Txikon, Ferran Latorre e altri :

Tom Ballard

Le sei grandi pareti Nord in invernale, solo :

Drytooling, la via più difficile al mondo :

Tomek Mackiewicz

(4) il lungo post dopo la spedizione 2016, le polemiche sulla vetta, i messaggi satellitari di Moro sul maltempo :

http://czapkins.blogspot.com/2016/06/witajcie.html

Alessandra Carati

Intervista a Radio 24, podcast, con Alessandro Milan (dal minuto 44:00 in avanti):

Simone Moro

su Mummery, Nardi e Ballard

su Nardi , 2016 expedition

https://www.montagna.tv/93793/nanga-parbat-la-verita-di-simone-moro-a-filippo-facci/

http://alpinistiemontagne.gazzetta.it/2016/11/28/come-si-arrivo-alla-rottura-con-nardi/

Reinhold Messner

Mckiewicz/Revol e il tentativo di vetta abbandonato per maltempo

(1) 19 Gennaio: “Giorni decisivi sul Nanga.Tomek Mackiewicz ed Elizabeth Revol hanno individuato il colouir che conduce alla piramide di vetta[..]”

https://m.facebook.com/groups/185186314867223?view=permalink&id=1058684744184038

https://m.facebook.com/groups/

(5) le previsioni di quei giorni :

sulla tragedia al Mummery

http://montagnamagica.com/la-tragedia-sullo-sperone-mummery-fanatismi-e-alpinismi/

[:en]

THE PERFECT ROUTE

The book : Review

“The Perfect Way / Nanga Parbat : Mummery Spur” is the posthumous book by Daniele Nardi, written with Alessandra Carati (writer, editor and screenwriter) released in November 2019 for Einaudi , available only in italian edition.

The tragic death of the italian mountaineer and his English partner Tom Ballard at the end of February 2019 on the Mummery Spur of Nanga Parbat, has transformed what was to be the story of a long journey towards a dream, into an intimate autobiography, full of self-criticism, sincere and conscious, raw in the contradictions and bitter in the narrative of conflicts and recriminations with others ; at the same time, full of an unstoppable passion, full of love for his wife, friendship, esteem and respect towards the mountaineers with whom Daniele Nardi shared challenging climbs, successes and failures. A story full of falls and subsequent redemptions, against adversity far more fearsome than some Himalayan wall : diseases, both physical as psychic. All of this, narrated between mountaineering feats of increasing thickness, maybe not outstanding but often in remote environments, with real exploration, especially on less famous but iconic and difficult peaks between 6000 or 7000 meters, both in Karakorum as in Himalaya.

The heavy emotional and moral burden of completing and publishing the book was taken on the shoulders of Alessandra Carati : without previous particular passion for the Mountains, much less towards extreme mountaineering, her acquaintance with Daniele Nardi – and with his family, his native environment – had turned into a friendship that led her to embark on the difficult winter trek to the Base Camp of Nanga Parbat, to share some days with . Alessandra wanted, not without hesitation and problems, to really try what extreme winter mountaineering meant. The motivation, she explained us in the following interview, was to understand what drives a man to live in brutal winter conditions, on colossal mountains. Nardi, in those days, showed her and then sent her an email saying that if he didn’t come back from the mountain he wanted her to finish writing the book.

“Because I want the world to know my story”

The first, clear feeling at the end of the reading, is that Nardi has written a sincere story, a true “naked self portrait” – unlike most books written by mountaineers, full of rhetoric, self-celebration or boring lessons of motivation , often lacking in self-analysis, a sight on their own contradictions and human miseries. This, together with the beautiful narrative style, is quite extraordinary, since one of Daniele Nardi’s biggest problems has always been the style of communication : often Gascon and slash, full of drama, over the top, bitter and sometimes lamenting, for the syndrome of isolation always suffered, he mountaineer “de Roma” [“born/of Rome”,ndR ] , nicknamed “Romoletto” [“the little king of Rome”,ndR] by Silvio Mondinelli, against the Northern Italian Alpinism entourage, With few sponsors and great difficulties in financing their own businesses.

It is certainly thanks to the great craft of Alessandra Carati that the reading flows pleasant, pressing and exciting; the narrative system is well structured on the five attempts to climb the Mummery Spur of Nanga Parbat, the large index of rock that points straight to the summit from the base of the Diamir, surrounded by drainage channels, overlooked by huge glacial evenings, accessible only by a dangerous and cracked glacier. The beginning of these attempts is represented by an email, affectionate and concerned, of a friend of Nardi, the great Canadian mountaineer Louis Rousseau, who tries to dissuade the italian from the Project of the Mummery, with touching and impressive words and motivations.

The Mummery : dream and obsession of Daniele Nardi, around which the rest of life flows and takes place; for each of these trials, the mountaineer’s thoughtful gaze on the Diamir wall shifts and lingers on the events of his life, his training as a mountaineer, the first solitary on the Grandes Jorasses at 19, the result of an irrepressible and early passion, developed during the family’s summer holidays in the Alps, and matured almost as a self-taught, even on the crumbly and not easy northern walls of the Central Apennine, on the Gran Sasso and on the Shirt.

Able to reach Everest in 2004, albeit with oxygen, then the middle peak of Shisha Pangma without oxygen. In 2006 he climbed Nanga Parbat via Kinshofer route and Broad Peak. In 2007 he was a expedition leader on K2 and climbed to the summit without oxygen – but a fellow expeditioner, Stefano Zavka, never returns from the mountain, having reached the summit well after sunset.

The book shows Nardi’s self-criticism, inexperienced in emergency management and especially the “after”, in communicating what happened to Zavka’s family. A ghost that will accompany him for a long time. The book continues with dry tales of past successes, does not linger on the mountaineering description of the climbs – except for the one that Daniele Nardi loved most, the new route traced on Baghirathi III with Roberto Dalle Monache, way not finished on the summit but remarkable in its development and difficulties on one of the most beautiful and coveted Himalayan peaks.

Paradoxically, winning the prestigious Italian Alpine Academic Club Council Award for this route, Nardi writes in the book that here begin “interference” to the pure love for the exploration of the high mountain : his desire to feel accepted and recognized by an environment that does not consider it as much as it would like, its desire for revenge, the need for visibility begin to affect its mind.

The story of the attempts to realize his dream, the way of the Mummery Spur- a goal for which he was mocked, blamed as suicidal, exalted, deluded even after death – continues between beautiful pages of mountain : especially in the story of the first attempt, 2013, teamed up with the great French mountaineer Elizabeth Revol; The duo reached the highest point ever reached on the Mummery, 6450 meters, about 250 meters from the end of the technical difficulties and the exit of the Sperone on the “great basin”, the plateau at 7000 meters, between the impressive columns, severe and dangerous, of the glacial evenings Incumbent. Then some words on the missed teaming up with Tomek Mackiewicz and Elizabeth Revol, the conflict of visions and objectives that separates them at Diamir Base Camp; conflict that is mitigated, by the fine words that Nardi reserves to both, full of great affection and esteem.

The fourth chapter – dedicated to the resounding breakage with Alex Txikon and Ali Sadpara at the beginning of 2016 , his partners on previous year during the attempt of First Winter, failed two hundred meters below the summit – is a very detailed account of an “announced conflict” : the Nardi’s attempts at mediation between Bielecki and Txikon, being the spanish worried by economical trouble, the incident on the wall where he saved the life of Bielecki himself ; Nardi’s obvious lack of motivation for Kinshofer route, the first conflicts with Txikon and Sadpara and mutual distrust, immediately, with Simone Moro ; the failure of Elizabeth Revol and Tomek Mackiewitz bid, when at about 7300 meters, with the concrete prospect of a successful summit through the Messner-Eisendle route, they retreated after receiving from Moro weather forecasts revealed to be quite incorrect, perhaps the strangest event that year . This, confirmed by Filippo Thiery, meteorologist of Nardi, who told him that good weather was expected for 3 days ; he did not understand how Karl Gabl – a renowned meteorologist, Moro trusted expert – could have failed those forecasts [see the forecasts of these days]. While the French and the Polish quickly descended on January 22th, on January 25th Nardi, Txikon and Sadpara were at C3, at 6700meters, in good weather. And the Revol left the Nanga: she ran out of expedition time. The polemic and breaking tail between Mackiewicz and Moro was even bitterer [see Sources (1),(2),(3),(4),(5) below]

Then Moro and Lunger’s decision to join Kinshofer route. Daniele Nardi waited three years before explaining how he felt he came first to the decision, then to the break with the rest of the team, handing Carati the recordings of the dialogues at Base Camp and its version. Absolutely questionable version, of course, and biased : but in the book there is also this. And there is further criticism of Moro for letting Tamara Lunger retreat alone, in distress, on the fateful day of the First Winter on Nanga Parbat.

At the time, following that daily expedition, I was not surprised by the distrust of Nardi by Txikon, Sadpara and finally Simone Moro, until his ousting from the team . But no one emerges undepended from errors and ambiguous behaviors, in this chapter, albeit with different nuances. It is, of course, his own version: however, and it’s not negligible, the dialogues are faithful transcriptions of audio recordings – Nardi admitted it was questionable, but not illegal – according to the co-author and that the publisher Einaudi considered their publication lawful and transparent.

To date, several articles from the specialized press on the book have been published; it is curious, euphemistically speaking, to note that any journalist had the curiosity to speak about or ask questions about this uncomfortable, bitter, questionable chapter which is an important part of the book that Nardi wrote.

Is up to the reader each thought or judgment on his own, about an issue that will no longer change anything : History is written and has erased old controversies. Nevertheless, this chapter of Nardi’s life reveals an unpleasant side that is generally preferred to conceal; it strips mountaineering from its supposed idealization, its being not exempt, as no human social activity is, from great rivalries, dirty games, miseries and opportunism. On the contrary: it amplifies to the extent of merits, qualities and fears, defects. Of all, no one excluded.

Certainly, Nardi was not capable of diplomacy and self-control confronting with more experienced climbers, during expedition. He paid a high price for this, even in terms of credibility. It must be said.

Tom Ballard and Daniele Nardi. Nanga Parbat

Tom Ballard and Daniele Nardi. Nanga Parbat

The chapter of the “Fourth Attempt” continues with the story of the acquaintance with Tom Ballard, who sought Daniele Nardi, interested in his type of mountaineering: a friendship that was welded in 2017, in a interesting expedition to the remote Kondus Glacier, in Karakorum ; the duo climbed a rock route on an unknown 6000 peak in the Area, and an attempt on an iconic 7000 meter mountain, the Link Sar. The pair, after having opened over 1500 meters through a tricky glacier , until the first difficulties of the North East wall, will have to withdraw due to continuous avalanches and bad weather. Then there is the painful chapter of the Tomek tragedy and the rescue of Elizabeth on Nanga Parbat winter early 2018, when Daniele contributed concretely to the rescue efforts, coordinating and involving all his Pakistani contacts and providing useful information. The thoughts about Tomek, his personality and his intimate dreamer soul are very touching.

In the final chapter, the book’s narrative register changes: Alessandra Carati tells the story in the first person.

She retraces the trek to Base Camp, the difficulties and the frost, her intimate experience as a woman in the relationship with the locals, the enormous esteem and respect that all Pakistanis pay to Daniel, the delivery of materials and humanitarian goods in the very poor villages between Skardu and Diamir Valley; the friendship and good humour between Tom and Daniel, the fearful avalanche rumbles that dumped the mountain “whose bulk covers the sky and overwhelms you immensely”. Then the return to Italy, Daniel’s confident messages and those worried about the material buried by the avalanches.

Until the decisive moment : there is a window of discreet time, it is February 22nd, now for a month now the two are stopped at Base Camp, training on the sass doing drytooling, walking up only to Camp 1. They start with great determination, until the fateful 24th February, where they climb 300 meters of speron from the 6000m of the C4, a curtain in the wall. They are optimistic, full of joy that they communicate to Alessandra for satellite, they found the sack hanging on the wall, at the top. But they tried perhaps too much in the previous two days, with a pull and so much load of materials for the decisive attack. And the final hours, the silence.

The epilogue we know, Alex Txikon generously leaves K2 with a team to rescue and search for Daniel and Tom. After terrible days, between reconnaissance on foot and with drones, while a bad media debate rages, where Messner, then Moro and others claim the safety that the two were buried by an avalanche, that the road was almost suicidal [ see links in Sources] Tom was involved in a feat which was not his own and was not to be done as the first experience out of a 8000ers peak, the fan-tribes dividing and arguing on Social etc – the two unfortunate climbers were spotted by telescope, dead, not killed by an avalanche but hanging on the ropes, in perfect visibility even after 10 days since the accident, probably victims of a rappel accident and/or hypothermia. Their last phone call was reportedly at 8 pm on February 24th, at Base Camp: Daniel said they were coming down the wall, the conditions were terrible. Whatever the reason for leaving the tent and knowing that probably hypothermia was waiting for them into darkness, it was obviously a tragic , extreme and ultimate necessity.

The short epilogue is a touching testimony of life, of pure and sublime sensations on the Nanga and ends like this:

“at least once in a lifetime, everyone should meet a Daniele Nardi who with a smile urges you to go and see what there is beyond the line of the horizon, and to walk with him on the glacier”

Daniele Nardi came out of the scene with his flaws, his humanity as abrupt, distrustful, difficult and sometime ambiguous ; at the same time, as expansive, positive, full of love and an irrepressible passion for mountaineering and constant challenge in facing oneself’s demons. A burning passion that costed him a short life, but not lived unconscious .

A life that deserves respect, which arouses and provokes discussions but a worthy life: a man, a mountaineer who had courage both in the mountains and in testifying, above all, of his most intimate weaknesses without stopping to think positive, to try to get up at every fall to start over and improve; that in the history of Mountaineering will remain as the one who attempted “an incredible winter route, a direttissima, a fucking visionary route on one of the most feared mountains in the world” – as the mountaineer Louis Rousseau wrote to us: the Mummery Spur Route .

Interview with co-author : Alessandra Carati

Alessandra, yours is a solid resume of writing experiences for film and theatre and then as editor and ghost writer on very varied publishing projects; in 2016 you co-authored, with the cyclist Danilo Di Luca, of his autobiographical book “Beasts of Victory”, a harsh act of accusation (and self-incrimination) , of those who no longer have anything to lose and can finally speak in true freedom of the “system” against the huge problem of doping, an intimate unveiling of an athlete who confronts the hypocrisy of those who expelled him from the environment (disqualified for life) as a unique scapegoat of what seems an intolerable tangle of collective interests in sport.

I mention your literary curriculum because I have the idea that in part the meeting with Daniele Nardi has involved you and convinced you to work with him, for his experience – equally problematic, also for several reasons – in the environment to which he dedicated his life : Mountaineering. Is that so? What was, however, the decisive drive – for an author absolutely distant and not involved by a personal passion for the mountains – to undertake the writing of a book with a mountaineer ?

When I approached Daniel’s story, I didn’t know mountaineering and I didn’t know anything about the quality of the environment. I chose to embrace the project because Daniel intrigued me. As I wrote in the book and like many other people, I wondered why someone chose to test themselves so a mountain of 8000 meters, in winter, five times in a row. I wanted to understand what moved him, intimately and as a human being.

Reading the book, I found Daniel’s courage extraordinary for Daniel’s raw and sincere self-analysis, which spares no unpublished details about his period of depression and burnout, he does not discount mistakes in private life as well as those in some shipments, because of his character. Yet, the positive side, of pure sincere, gascon and empathetic passion emerges and is appreciated. How did you experience this contradictory aspect of Daniel?

Daniel was so many things together. Writing, fortunately, resists the temptation to simplisticly reduce people and protects against judgment. In doing so, it allows us to understand more, to accept more, to love more.

While working on the book, did you have to argue with him about how he wanted to expose his emotions, his ideas and the events that happened in the great mountains of Karakorum and the Himalayas?

There was no time to discuss the form with which to build the narrative. We worked together in the collection and choice of materials, then I proceeded to write alone, with all the decisions that come with it.

I cannot avoid to address to you a very sensitive and burning issue. Since the book came out, I have read articles and reviews but for anyone who has read it, there has been an almost total and deafening silence on a precise part: The Attempt Four, that is the 2015-2016 expedition with Txikon and Sadpara, lived between bitter polemics ; what surprised him, at the time, is that Daniel defended himself very tenaciously only from the accusations of Txikon (later turned out to be rather labile and unfounded) of non-financial contribution or even of having “invented” the fall on the Kinshofer wall . Daniel did not respond, punctually, to Moro’s strong accusations.This weighed heavily in the collective judgment towards him. As Daniel himself writes.

In the book it’s striking to read the brutal and polemical dialogues of what happened. And these dialogues differ from Moro and Txikon’s versions. I listened to your interview on Alessandro Milan’s broadcast on Radio24, where you say that the dialogues are written “to the comma” because they come from the recordings that Nardi made in the common tent, while the final meeting was taking place with all others. You said this was not illegal at all, so much so that Einaudi has assessed it as publishable without censorship. Do you confirm that? Has anyone contacted you to specify or disprove what is written? What do you think of the reaction of the press, by the way?

The scenes of the fourth attempt, which take place in the tent and which include Simone Moro, Alex Txikon, Tamara Lunger, Ali Sadpara and of course Daniele, have been reconstructed entirely from the recordings that Daniel had made. I did not draw the jokes and their content from a story mediated by Daniel, but directly and faithfully from the audio. They are the voices of the protagonists.

For example, there is a detail of the story on which conflicting versions have been given, and it is the way it happen the join the two expeditions. Moro stated publicly, in his book “Nanga” and in some interviews, to have been invited by Alex Txikon, while in the audio he repeats several times that it is he who asks to be allowed to join the Kinshofer team, so much so that it insists on how much money has to pay for the material and the work done in equipping the mountain. It is a subtle, yet substantial, difference because it defines the relationships of force, weights and the balance within the team that will attempt the first winter of Nanga Parbat.

No one has so far asked in any way for that part of the book, much less talked about it on printed reviews. Honestly, if I were a journalist, I’d be intrigued, I’d ask questions.

Let’s talk about to the most exciting and painful part, the one you practically wrote yourself. The final attempt: your decision to trek and spend days at Base Camp to really experience a winter expedition; the atmosphere between Daniel and Tom, the long waits and the tragic ending. How did you go through those terrible days? Have you thought about quitting everything, despite Daniel’s request in his famous email?

During the weeks of the rescue the project of the book did not even touch me, each energy, each thought were for Daniele and Tom. I was distressed to know how to lose them inside the gigantic Nanga massif. And then there was Daniela and Mattia [Nardi’s son,NdR], I couldn’t even imagine what they could feel at the time. Later I was tempted to let it go, but the will expressed by Daniele was very clear and his mandate nailed me. I gave him my word.

What conclusion, if ever, have you elaborated in your soul, about Daniel’s life and death?

I have no conclusions, no ideas, let alone opinions, about Daniel’s death. Everything I’ve touched, guessed and tried to shape is inside the book. Each reader can move from there to let the feeling with which to look at his figure, his life.

Interview with Louis Rousseau

Louis Rousseau is one of the strongest Canadian climbers. He was born in 1977 in Quebec and began to climb at 15 years old. Between 1999 and 2010 he climbed many peaks in the Andes, accumulating experience on the 6000ers. From 2007 he began to climb the great mountains of the Karakorum and the Himalayas, opening a partial new route on Nanga Parbat in 2009 ; he tried a new winter route on the South face of Gasherbrum I. He climbed Gasherbrum II, Broad Peak and attempted K2 several times. He climbed 7000ers peak as the Khan Tengri and the Tilicho Peak. Always without oxygen, pursuing the alpine style and following a very strong climbing ethic. His climbing partners on high altitude expeditions were Adam Bielecki, Gerfried Goschl, Alex Txikon, Rick Allen and many others.

How did you meet , if you did it live, with Daniele ?

I never met Daniele in person. Since 2015 we had sporadic contact via internet. I heard about Daniele after the 2011 Bhagirathi route and the 2013 winter attempt with Elizabeth Revol. After that, Alex Txikon contacted me to join him, Daniel and Ali Sadpara for the winter attempt of Nanga Parbat in 2016. I said no. Daniele invited me for the Nanga 2019 attempt but again I refuse and I tried to convince him no to go again. During the expedition we had regular contacts via WhatsApp especially when they lost a lot of equipment. I propose to send some equipment from my deposit in Pakistan. After all, it was ok, they had the essential to continue their ascent.

What do you think about Daniele, what impressions and feelings gave him to you – as climber first, then as a man?

Really motivated and goal oriented climber. He could climb hard technical routes as much as perform very well in high altitude. During our conversation, I could see that he was a real nice guy. Very idealistic and a dreamer who always want to improve and be a better version of himself. During our last conversation he told me one important thing, that he wanted: “to try to help people to change their life by inspiring them.» So for sure Daniele was a man who wanted to change the world around him, it was not about alpinism, collecting summits or seeking for first ascents, it was way more than about is own person.

I know he asked you to join in for his Nanga dream; then, you have some correspondence before telling him that you choose not to go in and asked him to rethink about it. Can you explain me, after your experience of a partial new-route on Nanga in 2009, what drove you to the feeling that you have done, with that mountain?

I will start my answer with something I wrote to Daniele : “You’ll find it a bit esoteric, but I believe in the curse of the killer mountain. There is something with Nanga Parbat that blinds us climbers and draws us even more towards danger compared to the other 8000m.” I think it is because of all the folklore around this mountain. When you start to read a lot about it, it turns into fascination and passion. It is really attractive and you want to go. Then, when I was there in 2009, two people lost their lives and there was a lot of discord after that. The recent history of winter attempts is also filled with discord, accidents, backstage games and now deaths. It is a real tragedy. There is no other words to describe the past few years. Just think of the 2013 terrorist attack. I saw Daniele go back into this again and I wanted to do something to discourage him. I asked him if he wanted to find a completely different and positive project with me, but he told me that : “if I change idea and I want to join him and Tom, to let him know.”

Do you think that danger starts, for a climber, in the moment he got too much emotional about a mountain, a goal ?

For a climber, danger starts as soon as he step inside the jeep that will bring him at the beginning of the trail going to base camp, that means at the very beginning of the expedition there is dangers. Mountaineering is an extremely dangerous sport. There are not many other sports in which you go on a vacation and you come back without your friend. Even if you are “too much emotional” about a project or a mountain, that does not mean that you are more in danger. Can this influence our decision-making? Certainly yes, or when there are other goals than climbing and feeling free, even goals that you don’t admit to yourself. You are always going to bring on an expedition the things that are not settled at home. Nothing that you will do in the mountains can resolve them, on the contrary.

I know that Daniele and Tom were professionals and they had the experience to climb Nanga Parbat in winter by a new route, but they unfortunately had a terrible accident. We will never know exactly what happened and it is terrible for the families. More than anything, we will never know their state of mind before the accident. Was it a distraction, was it a result of bad decisions like several accidents in the mountains? We do not know. What we do know is that the two climbers had strong experience and they completed each other very well in their team. Daniele had a solid high altitude and winter expedition background and Tom was one of the best technical climbers in the world. I don’t think their emotional state has anything to do with their death. It was a tragic accident.

References and Sources

Daniele Nardi

Nanga Parbat ed Elizabeth Revol, Mummery Spur 1st attempt : http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201212505/Nanga-Parbat-Diamir-Face-Mummery-Rib-winter-attempt

Translimes Expedition with Tom Ballard, Kondus Glacier, Link Sar :

Farol West,unclimbed peaks in Karakorum :

Baghirathi III :

Thalay Sagar, with Alex Txikon, Ferran Latorre e altri :

Tom Ballard

The Six Northern Alps Great Walls, winter , solo :

Drytooling, the most difficolt route so far :

Tomek Mackiewicz

The long post after 2016 Nanga Expedition :

http://czapkins.blogspot.com/2016/06/witajcie.html

Simone Moro

on Mummery, Nardi and Ballard

on Nardi , 2016 expedition

https://www.montagna.tv/93793/nanga-parbat-la-verita-di-simone-moro-a-filippo-facci/

http://alpinistiemontagne.gazzetta.it/2016/11/28/come-si-arrivo-alla-rottura-con-nardi/

Reinhold Messner

Mckiewitz/Revol and the aborted summit bid due to ..bad weather

(1) 19th January 2016 : “Decisive days on Nanga.Tomek Mackiewitz & Elizabeth Revol spotted the colouir leading to the summit pyramidal [..]”

https://www.facebook.com/groups/185186314867223?view=permalink&id=1058684744184038

https://www.facebook.com/groups/

(5) weather forecasts during those days:

about Mummery tragedy, previously published

http://montagnamagica.com/la-tragedia-sullo-sperone-mummery-fanatismi-e-alpinismi/

[:]